This post is something I planned writing since I finished making Together, a game I created with my wife Brena Cardoso during the Crossing Latitudes game jam. The reason for this is that I was able to test some ideas with this game and consolidated my workflow publishing web games on itch.io, but for everyone wanting to do the same, it's worth to know some of the "gotchas" they might get.

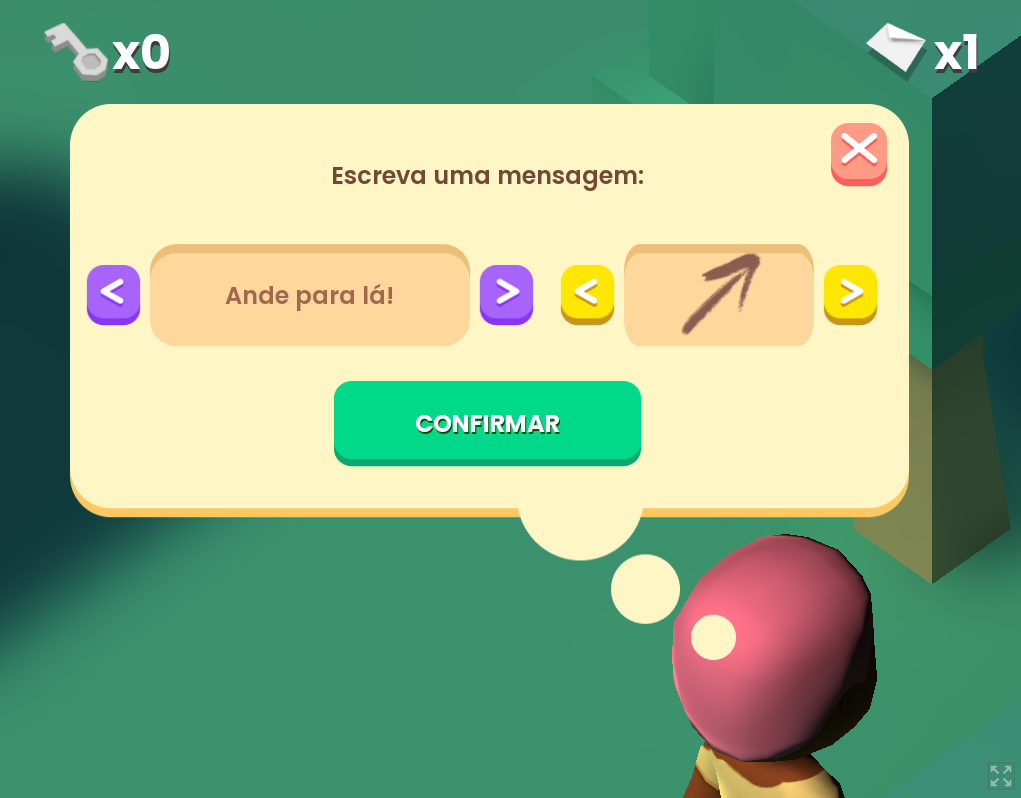

"Together" is an exploration and puzzle game, in which you have to find your path to climb a mountain. During the exploration, you collect letters you can use to write messages other players will see - but the message you write are always in a different language than the messages you'll read (Portuguese or Suomi). It's an asynchronous cooperation game, and we play around with the idea of the language barrier affecting the cooperation because that's one of the experiences me and Brena had having just moved to Helsinki from Brazil.

The idea of the game came naturally to us because when we heard about the jam, our minds were more-or-less settled on the idea of making a game that played with the language (since we just started taking Suomi classes). On the engineer side, I also wanted to use the jam to explore some topics:

So, let's dive in the results of each exploration a bit.

I knew we were going to make a template system for the messages, similar to Dark Souls. So the server needs to store the messages each player sends with:

This is only relevant to the client to parse the messages, the server actually just stores a string with the message content concatenated. For example, if a client posts a message on position (10, 15, 20) with options 1 and 2, the server will store the following string:

"1;2;10.00;15.00;20.00"

When a client receives this message, it will parse it for the message options chosen and it's position, and it will spawn a "letter" object in that position.

How and when the players would receive messages followed a simple logic:

This solution have obvious (but minor) problems I chose to ignore (because Game Jam):

My workflow is based on the amazing tutorial by Sean Schertell on how to deploy SvelteKit apps (I used it for Mastonews). This is a brilliant guide because it gives you the basic sysadmin workflow to setup a single and very simple server. You can use it for pretty much anything, not only SvelteKit! It also showed me Caddy, which for someone that head nightmares with nginx broken configurations, was the one thing that convinced me that "hey creating servers is not actually that difficult!".

I knew that for this particular game, I'd only need a server with an SQLite database to write player messages, and from where the players would query for messages to display on their game. This would be super simple to make if it wasn't for the one "itch.io" gotcha:

Browser games in itch.io HAVE to use SSL for any request.

You don't need to understand how SSL works, but you already seen it: any (most) websites nowadays use "HTTPS://" - not "HTTP://". "HTTPS" is a site with SSL set and a certificate that guarantees the communication between client (e.g. a game) and the server is secure (as in, no one will be able to "eavesdrop" the communication). Itch.io understandably enforces SSL on browser games for security reasons, but that means you have to set SSL on your server if you want to make a game that communicates with your server. Setting up SSL means two things:

In my case, I've already bought "illusionfisherman.com" on GoDaddy. Caddy also automates the whole second step for me, so I literally only needed to follow the tutorial I mentioned setting up the domain name as "illusionfisherman.com" and that was it, server was ready to communicate with client.

The server itself is just a Node with better-sqlite, a JS package that is extremely straightforward and easy-to-use to deal with local SQLite databases. It's running on a pm2 process, an awesome process manager that I also discovered following the tutorial I mentioned (Sean Schertell: if you ever read this, THANK YOU).

The second "gotcha" is setting up an encryption method for the messages between client and server, something the players themselves can't easily hack. I don't think this is something that would affect this game in particular, but I've seen players hacking leaderboards quite easily on other Game Jams, and I wanted to explore at least a simple encryption method between players and servers to avoid this kind of scenario in the future.

(A quick side-note: SSL is an encryption layer, but it's not helpful in the case of local players hacking the messages being sent to the server, because they are able to check and interfere with the message BEFORE it is encrypted by SSL)

I tested some things, but by far the easiest (to develop) solution I found was:

A SHA256 string hash can be thought as a way to translate a string to an "unique" byte sequence. That means that the chance of two different strings to share the same hash is almost impossible (to the point of being irrelevant to be considered in the case of this game), and since the "secret string key" is not published anywhere but in the game's code and the website code, this is sufficient to "guarantee" that a message wasn't tempered with (unless the hacker knows the secret string key).

This is not a perfect solution, but it's a solution with a "good enough" hacking friction that makes the game at least not trivially hackable.

The second challenge was to make a game that was pretty, but small and efficient to run in browser. I had a couple of ideas in mind:

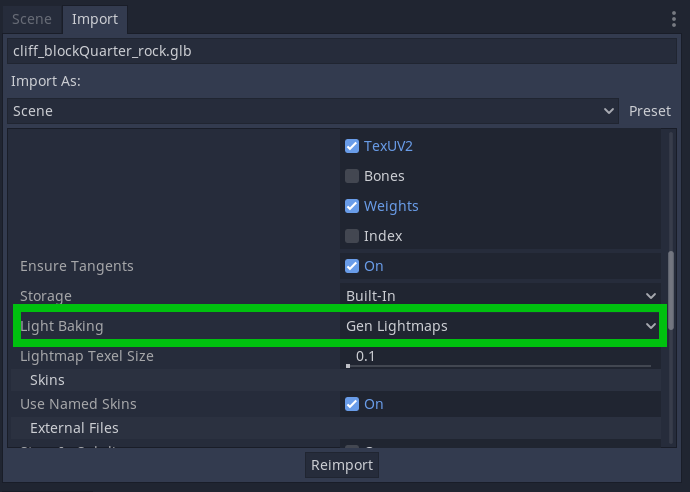

This is something I learned working at GDQuest, but the ideal 3D workflow on Godot is to use .glb models with the least amount of changes (avoiding using inherited scenes or changing them in .tscn files). The reason for that is that when you inherit the .glb models and make changes to it in .tscn files, you are serializing the model (and the changes you made) to text format, which can make the exported binary of the game much bigger. This is better explained here: https://github.com/gdquest-demos/godot-4-3d-third-person-controller/pull/30.

Since me and my wife used some of the Kenney assets, the trick was to add a "Post import script" to the 3D models that would do the following:

This also made my life easier whenever we changed some of the models - I only needed to change the model file and reimport it, since the only dependencies were scenes that were adding the ".glb" file directly into their node tree.

This wasn't the first time I tried baking a lightmap in Godot, but it was the first time the assets workflow made it easy enough to bake lightmaps. What I had to understand is that reimporting assets with the settings you want is, most of the time, better than changing settings on an inherited scene. This is also true for generating lightmap UV2 in Godot.

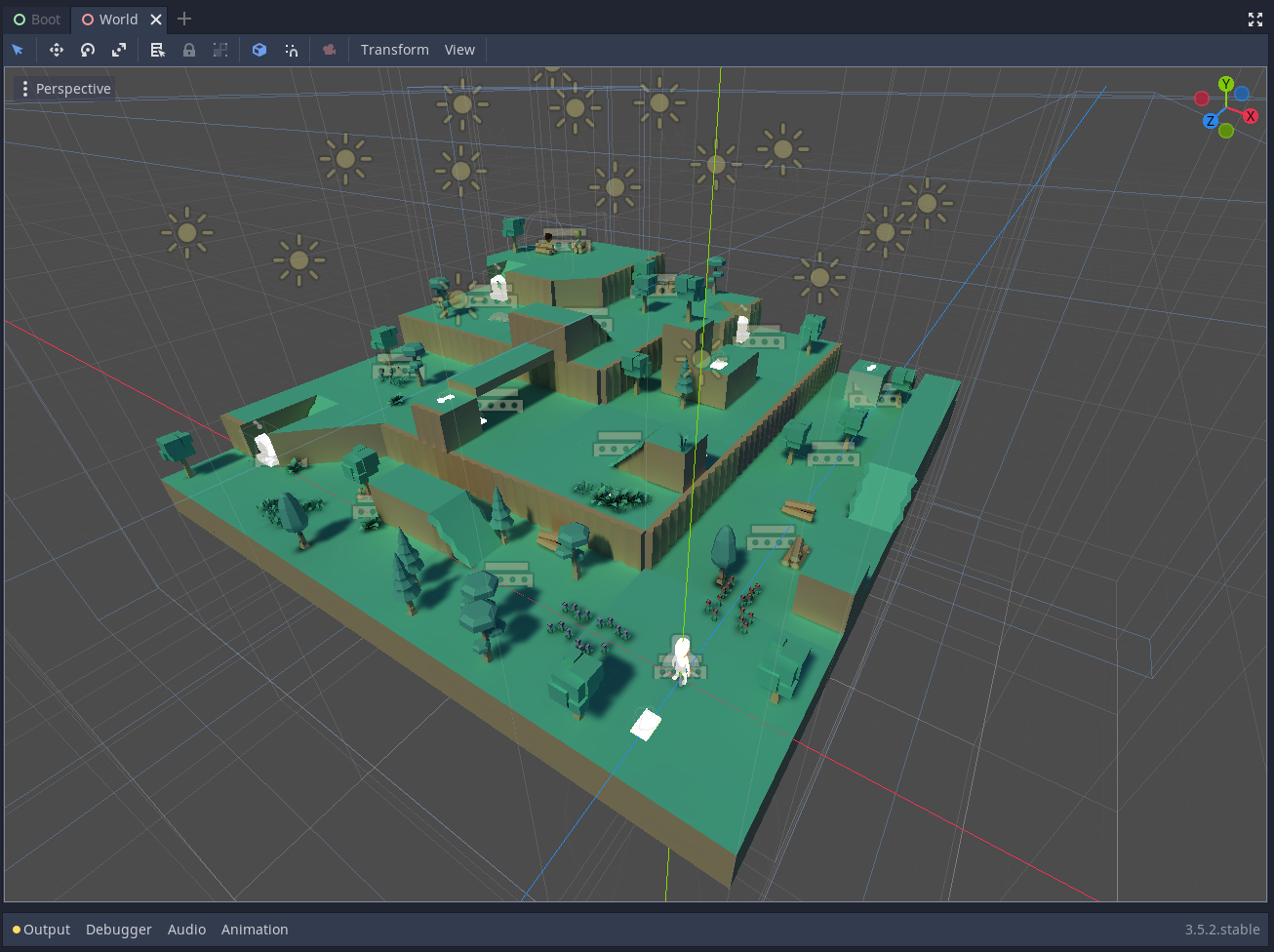

My workflow was to bake single regions of the game:

And have a "world" scene that would control which level the player was in, and show/hide levels accordingly:

This is a similar workflow I had for a metroidvania game I made for Metroidvania Month 17. Having the entire level already instantiated is not optimal but the level is small enough to not make a difference - but having the entire world visible to you is REALLY helpful in designing the game.

I feel I was a bit greedy at the start of the jam, because me and my wife had Boring Stuff (tm) to do during the jam time, so we'd have less time than we wanted to make the game. But things got aligned surprisingly quickly, and the engineer workflow I had in mind worked really well. Brena is also amazing at adapting the assets and animations we found, and creating new assets ad-hoc.

The end result is a game that works really well in the browser, smaller than most games I made before (some of them even simpler than "Together"), but packing quite a bit of development love from me and Brena.